The

shock of seeing the site where he will be responsible for building a

mission does not wear off as they ride down into the valley the

natives call Comondú.

There is no trail, just a worn-out series of grooves in the stony

earth where game and the Indians have traveled.

Towering

palms and other trees signal the presence of the rarest commodity in

this barren land – water. It bubbles up out of the earth at the

base of a cliff forming a large pool which then turns into a stream

flowing down the valley. The spring is filled with roots and other

plants and there is no doubt that great effort will be needed to

clear it out. The area surrounding it is thick with tall reeds. If

necessary, they can be used to thatch roofs. Father Mayorga looks

around and smiles when one of the converts points out signs of

various animals that have come to drink. He has never hunted an

animal in his life but pays close attention as Father Ugarte has

warned him that being aware of what is around one makes the

difference between life and death. To him and his converts.

“El

Señor Reverendo Padre,

see this?” The guide points to a series of large tracks with

pointed slits in the front. When Mayorga nods, the Cochimi says, “Es

el Tigre, Señor.

She bring babies here to drink. See small marks?”

Mayorga

looks around and wonders if the big cat is nearby.

Seeing

the priest's concern, the Cochimi's lips turn up in a faint smile and

he assures the priest the cat and her cubs are far away. He then

places a finger to his lips and points to a nearby boulder where

something lays in a coil. “Vibora,”

he whispers. “Mordida

veneno.”

Mayorga

holds very still, having learned the snake with rattles on its tail

is not something to be trifled with. He relaxes as the snake lowers

its head, uncoils, and swiftly glides deeper into the rocks.

Father

Ugarte previously surveyed the site and knows exactly where he want

the mission sited. “Our first order of business is to ensure water

to irrigate the crops.” He points to a spot along the stream,

indicating it is where boulders should be placed to hold back the

water so it can be diverted into the irrigation ditches. He then

leads the way about two hundred paces downstream to a place where the

land is elevated above the stream bed.

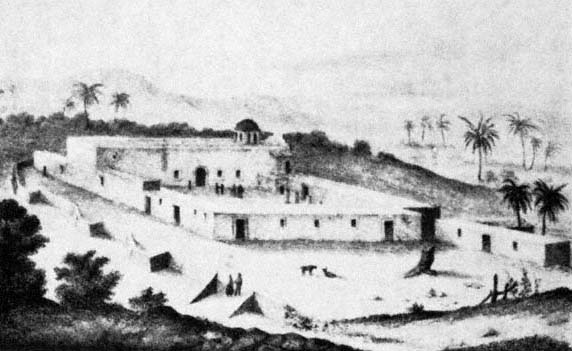

“Here

is where the chapel, your quarters, and the storehouse will be

built.” He explains how it is safely above the level of water in

the event severe rains in the mountains cause it to overflow its

banks.

Father

Mayorga has learned enough to identify where the gardens will be laid

out as the earth appears less sandy, but not of heavy clay. The area

has a large growth of grasses and he understands some of it must be

cleared away to till the soil. Other grassland must be kept to

provide feed for the livestock Father Ugarte will bring from Misión

San Javier.

The

Ancón,

as the Cochimi call it, is a shelf filled with black, lava rock. Some

of the stones glisten their ebony shades caused by cooling. Andrade,

the guide, grins and shows Father Mayorga his knife made of similar

stone. When offered, the priest carefully tests it with his thumb,

finding the jagged blade quite sharp. One of the things he learned at

the college in Mexico City was the deadly efficiency of native

weapons made of obsidian.

The

mule train contains everything needed to create the mission. But,

there are no hands to do the construction so they can be safely

stored. Father Visitador Salvatierra solves that by ordering all

members of the group to gather rocks and boulders and carry them to a

spot he selects. He draws lines in the hard-packed dirt and trenches

are quickly dug.

The

moon is full in the starry sky and, after a humble evening meal and

prayers, work continues. As soon as the trenches are completed, they

are filled with large boulders, rocks packed into the cracks and then

sealed with mud from the stream banks. Only when the moon lowers and

the night dims do the workers find spots on the sand to nestle into

their sleeping blankets.

A

storehouse stands before them by midday and goods from the packs are

taken inside to be carefully arranged. Stones packed over the wooden

frame strengthen the door and a lock is placed into the hasp to

ensure the goods will be safe from curious hands.

Speaking

of which? Father Julián

gazes around all the while he toils to see if any of the Gentiles

have come to see what the activity is in their valley. Maybe he is

not clear on what to look for, but he sees no signs at all. Had they

not begged the father visitador and Father Ugarte for a mission of

their own?

The

most important steps comes after the goods are safely stored - the

outlining of the chapel. It will be aligned so the door faces the

rising sun. Once that is accomplished, a cairn of rocks is raised

with a plain wood cross on top.

Incense

is used to purify the site as the father visitador swings the

thurible, chanting prayers while he does so. Holy water is then

sprinkled on the spot where the altar will stand and it is announced

the site is dedicated to Saint Joseph.

The

soldiers and neophytes, with the others supervising and lending a

hand, set about leveling the ground and covering it with tightly

packed stones and pebbles, also filling in the trenches to start

construction of the chapel walls.

Poor

Father Mayorga has never dreamed of being a stonemason. Conducting

holy rites and teaching people the mystical beliefs of the church are

what he envisioned when he first decided to take the vows of the

order. Always of ill health, the physical effort of selecting and

carrying stones to the site does not bode well for him and, to his

shame, he must often pause to rest.

The

other fathers and even Captain Rodriguez bend their backs to the

task, setting an example for the soldiers, servants, and neophytes.

Much

to the pleasure of all, two Cochimi women and their children come to

stand apart, watching the newcomers toiling in their area. Father

Mayorga cannot control himself and gazes sideways upon the all but

naked female bodies, agonizing over the unholy lusts overcoming him.

He turns away in shame and mutters prayers begging The Lord God to

forgive him.

He

does not notice both Father Visitador Salvatierra and Father Ugarte

doing the same.

Wood

brought for the purpose is used to frame windows about ten feet high

on the walls, along with the door leading into the chapel and another

smaller one behind the altar area leading into the sacristy. Once

filled with stones, the wood is removed so a form of adobe

can be laid to hold them in place.

Father

Mayorga is surprised at how the other fathers easily form the walls

to be thicker at the bottom, tapering to the top with notches to

support palm logs cut to span the chapel area and support a roof of

palm fronds.

Seven

days pass until the altar is erected, the marble slab brought from

far away Spain uncrated and set upon the stands. Once again, the

incense is used to purify the area along with appropriate prayers and

the crucifix is placed in the arched niche on the wall behind it.

Intricately carved wooden plaques are affixed on the walls for the

Stations of the Cross and a statue of Saint Joseph is placed in a

smaller niche on the southern wall while the Virgin of Guadalupe is

placed in another on the opposite wall.

A

time will come when the interior and exterior walls will be covered

with stucco, but there

is no time for it at the moment.

The

others must depart and Father Mayorga will find himself in that

lonely place with but Private Juan Morales, the soldier assigned to

be his companion and helper. He is fearful, but sets it aside to

strengthen his belief that he and Morales are in God's hands.

Morales

is a Criollo from Guadalajara and has been in California for five

years. He is married, but his wife and two children are staying in

Loreto until the first crops are ready for harvest.

The

first Mass conducted in the chapel of Misión San José de

Comondú by Father Mayorga is

before the two other Jesuits, Captain Rodríguez, and the rest who

have helped start it. Juan Morales acts as his assistant and he is

most pleased the soldier knows the Mass so well that he need not be

instructed in what to do.

Much

to his surprise, the Cochimi women stand in the back of the chapel,

their children clutching their legs. They clearly have no idea what

is happening, but appear to be impressed by the incantations and

ringing of bells.

The

others say their farewells at the end of Mass, each father returning

to their own missions while Captain Rodríguez goes back to Loreto.

“What

do we now, my son?”

Morales

smiles, pleased the father seeks his advice. “We prepare a place

for us to dwell while we take the next steps in making this a

productive place.” He then pointed across the stream. “See. The

Cochimi women do the same.”

The

Indians busily gather limbs cut from acacias, along with twigs to

construct their open-air shelters that only provide shade from the

blazing sun. Cutting their own limbs is far easier and faster with

the sharp steel blade Morales wears on his belt.

They

have barely hauled the wood to where they wish to build their shelter

when the two women approach. The elder says something and Morales

grunts and withdraws. “She says it is her place to do this. Not

ours.”

Mayorga

nods. Although he has not been in the area very long, he has studied

their language with great intensity as it is the only way he will be

able to teach them the things needed to bring them to The Lord.

The

Cochimi language is very simple and Mayorga is in awe of how the

other fathers have been able to translate the catechism and bible

stories into it. The natives have words only for those things they

can see, hear, feel, and smell. Abstract ideas and emotions mean

nothing to them. As an example, a person or persons can be here or

there or far away. When a person dies, they are simply no longer here

or there. If they do not have words for death, how can they

understand the idea of resurrection?

“Come,

reverend father, there is something we should do.”

Mayorga

follows Morales to the storehouse and watches as he selects two

colorful wool blankets, some pretty beads, and two highly polished

pieces of metal that act as mirrors. They wait until the women finish

their new house and follow them to their camp across the stream. The

priest notices the children are gone and smiles when he sees them

return to the new house carrying armloads of wood for a fire.

Following

Morales's suggestions – the soldier would never dare to instruct

his superior to do anything - Mayorga lays out the blankets on the

ground and holds out the beads to the women. They giggle happily and

take them, placing them around their necks. Both are stunned the

first time they see themselves in the mirrors, chattering gaily as

they compare each other. They have only seen themselves reflected in

calm pools of water.

“Will

they understand if I give them Christian names?”

Morales

nods. “You can tell them you are giving them a sign of the all

powerful creator and it will have great meaning to them.”

The

older woman has a scar behind her left ear and Morales explains her

Cochimi name means Marked by Puma. Mayorga remembers Saint Catherine

of Alexandria who had been beheaded at the hands of the pagan emperor

Maxentius. “I shall name you Catarina,:” he tells her,

translating his Spanish into Cochimi with Morales's help. “She was

a woman of great bravery.” He fails to tell her that Saint

Catherine was a virgin.

The

other woman's elbow is unnaturally bent and Mayorga suspects it was

broken and not properly reset. Mayorga ponders at length, trying to

remember a saint who represents the infirm. The only one he can think

of is Saint Amalburga of Belgium whose patronage is for arm pain.

There is no similar name in Spanish and all he can come up with is

Amanda. Morales says it make sense to him and Mayorga signs the cross

on the woman's forehead as he had done for Catarina, announcing she

is now known as Amanda.

The

two women are overjoyed to have been given magical names by the all

powerful man in the strange black covering. They clearly cannot wait

to have their children so blessed with great magic, understanding the

great medicine man must first ponder upon it.

“They

will now stay here forever, reverend father. You have given them your

magic and will follow wherever you go.”

“But,

my son, where are the men? And boys?”

“They

wait in the hills until they see the power of our ways.”

“I

was told they begged Father Visitador Salvatierra to have a mission

here in their lands.”

Morales

chuckles, not meaning to be disrespectful to the priest. “They are

but little children, reverend father. They see new things and wish

them for themselves. But, it is not their way to toil as do we and

will have to find strong reasons to come and work as you and I.”

The

first order of business after the storehouse, chapel, and living

quarters is the zanja,

the vital channel to bring water from the stream to the gardens.

Creating that channel is going to be back-breaking work and Mayorga

wonders if his health will permit him to help the soldier.

Much

to his chagrin, the problem is quickly solved. Once Morales gets the

idea across to the women, Catarina turns and leaves the camp at a

lope. She soon returns with three boys nearing manhood. It is clear

they are hers and the priest explains what needs to be done. The

youths are unhappy, but not about to disobey their mother. Amanda

then runs off, soon returning with her two sons.

With

five pairs of less than willing hands to help, the task of clearing

the path for the trench begins. It cannot be straight due to large

boulders in the way, but Mayorga has an eye for such things and uses

a stick to draw a line in the ground for it to follow.

While

Morales bends his back to show the five youths what to do, the priest

turns to clearing stones and rocks from the plot of land chosen for

the first garden. It will be for planting the Three Sisters, the most

basic foods of a mission; corn, squash, and beans. The rocks and

stones are piled up to outline the plot and earth will fill in the

cracks so the water will soak into the earth before running off to

the next spot downhill where fruit trees will be planted.

There

will be yet one other major project and that will be digging a well

to provide drinking water to those who live at the mission. Even

though the stream flows well, Mayorga has been warned that days may

come when the stream dries up and the only water will come from the

well.

Catarina

and Amanda surprise the two Europeans by their ability to turn

cornmeal into masa

from which to make tortillas. That

is when Mayorga learns they had lived near Misión San

Javier and learned to make food

the Spanish way. Amanda tells Father Mayorga that is exactly why she

and her cousin had come to that place.

Days

pass quickly, both Father Mayorga and Juan seeking their sleeping

places sore and tired beyond belief. The soldier shakes his head in

amazement as the priest forgoes sleep to spend hours deep in prayer.

He is not surprised as all the other Jesuits to the same. They eat

the simplest of food, spends hours laboring or conducting rites, then

the remaining hours of each day in prayer.

How

do they survive in this terrible land?

A

runner comes to announce that Father Ugarte will soon be coming with

livestock and others to help.