I

encountered this question at a website called City Profile

I've

been very fortunate to have visited all 21 California missions –

plus three in Baja California. I have to admit that not any single

one is my “favorite.” To me, all of them are awesome.

Think

of it. In the late 1700s, men wearing gray robes enter an unknown

land occupied by thousands of naked savages waving spears, bows, and

arrows. Outnumbered, with a minimum of soldiers to protect them, the

friars located sites and materials, laid out the structure without

any degrees in architecture, and built them with the help of people

who had never dreamed of anything like agriculture or constructing

such structures.

What

about the numerous Indian slaves they had?

That

is one of the biggest lies foisted upon those interested in

California history!

Due

to the kindness and devotion shown by the friars, the Indians

willingly came to the various sites. Their work days were far, far

easier than any we experience now – more then two centuries later.

They attended morning prayers, ate breakfast better than what they'd

known before, spent two hours in religious instruction, worked for

two hours, then broke for lunch. That was followed by two more hours

of work, after which they were free to look after their own needs and

desires.

How

about the whippings to make them work?

Another

bald-faced lie!

Only

when the individual could no longer be verbally corrected did the

friars spank them as a parent would spank a child of their time. The

friars looked upon the Indians as children to whom they, as spiritual

leaders and parents, were responsible. As parents, they spanked their

children when necessary. A clear and inviolate rule was that no

punishment was to cause blood to flow, create crippling bruises, or

other harm. For proof, check out Hispanic California Revisited by the

Franciscan Press of Mission Santa Barbara. [Be it known, the friars

daily “punished” themselves far, far worse!]

So,

which is my favorite

San

Carlos Borromeo at Carmel due to its unique architecture and

beautiful interior – and that it served as the headquarters for the

Franciscan friars.

San

Gabriel Archangel as it was the biggest with the most productive

horse herds and livestock.

San

Juan Capistrano as it shows best the various mission industries.

San

Antonio de Padua which lies far from the beaten path and is probably

closest to what the missions were like in the late 1700s.

When

one considers what the Franciscan friars accomplished in the 18th

Century, one has to wonder how on earth they did it.

These

men came from modest families in the outer areas of Imperial Spain.

Even if their families were blooded and members of the aristocracy,

they certainly had little or no background in the crafts needed to

create self-supporting communities. What education they did received

was ecclesiastical. They studied the bible and the teachings of the

Catholic church. They spent more time kneeling in prayer than in

actual physical activities.

Like

Father Serra, most felt called upon to set forth to the New World, a

place of danger in which they saw the opportunity to bring heathens

to the Word of God. They endured dangerous journeys in leaky ships on

which they had little in the way of decent food. They landed on the

east coast of New Spain to be faced with a trek of several hundreds

of miles to a place where they continued their education in things

felt necessary to their calling.

I

must admit that this is a place where my research into this era falls

short. I have been unable to gather little information on the

Franciscan mission to the College of San Fernando. I am certain it is

contained in the archives somewhere but have yet found a source to

provide me with more than the bare essentials of a school for

missionaries.

Fathers

Serra, Palóu and Crespí were but three of many who passed through

the college to go on to places in Mexico [Majica as known to the

inhabitants of that land]. These three first went into the rugged

Sierra Gorda mountains. Eventually Father. Serra was made President

of five Sierra Gorda missions. He built the Church of Santiago de

Jalpan, which is still in use, and supervised the founding of the

four other churches. After being appointed as a professor at the

college, he once again was given the chance to conduct a mission in

Mexico. Father Serra's missionary activity during these years was

mostly in south and central Mexico, in what is modem Oaxaca, Morelia,

Puebla, and Guadalajara; the region east of Sierra Gorda; and in the

province of Mesquital, part of Mazatlan [eastern Mexico]. The work

was very exhausting, and the only rest he had was during the time

required to go from one town to another or the return to the college

after a mission. One time he was poisoned, someone putting

rattlesnake venom in the chalice. He refused an antidote but

recovered just the same.

But,

to continue about what the friars had to do besides teaching new

disciples and conducting holy rites. They were called upon to

construct European style buildings in a land where permanent

structures were unknown. The Indians lived in crude shelters made of

twigs, limbs and brush, open to the breezes. The friars had to find

the materials and shape them to be used for building not only places

of worship but places to live and conduct the various trades.

Then,

as if that were not enough, in order to put it all together, they had

to be carpenters, masons, potters, farmers, herders, veterinarians,

doctors, linguists, and teachers. Where on earth did they learn all

of this.

Reviewing

genealogy records for the period shows that most of the soldiers who

served with the friars at the missions were poorly-educated men who

had few skills beyond their military duties. Some were farmers and

all knew horsemanship and how to care for their animals. I guess this

is where the Indians learned to becomes such outstanding vaqueros in

such a short time.

Part

of learning so much about California history is having the bubbles

burst on some of the cherished stories I learned and loved about my

home state.

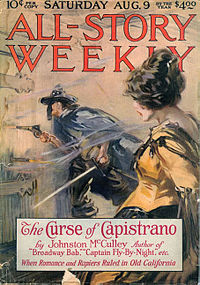

One

of them, of course, is Zorro, The Masked Avenger. A landed Spanish

Don, he rode forth to wrong the rights against the poor and

unprotected populace of Mexican California.

Oh

yeah?

It

turns out that Zorro, The Fox, is a fictional character from the mind

of a New York-based dime-book writer of the early 1900's, Johnston

McCulley.

What

a bummer. But, my research teaches me there were no Spanish Dons

[those holding Spanish royal titles] who owned the massive Rancheros

in early California. The huge land grants were handed out to private

soldiers who had completed their enlistments in lieu of a lot of pay

they had not received from the Royal Treasury. There were a couple of

officers who received grants but they were Criollos, Spanish/Indians

born in the New World. These soldiers often “hired” local Indians

to work for them, their pay being in the form of food, clothing,

housing, and animals.

Another

myth was of the famous/infamous bandit Juan Murietta. I went to high

school in Redlands, not far from a place called Murietta Hot Springs.

I always thought that was perhaps one of his hideouts from the

terrible American posses sent out to hunt this brave defender of

Mexican rights. I learned not a lot of truth is known about this

historical figure. Some say he was part Cherokee and part Spanish

peon run away from sugar cane plantations in the American southeast.

I also discovered there was little heroic or patriotic about him. He

was an out and out cutthroat thief and murderer of the lowest order.

Another

is how land grants were measured. Somewhere, I heard the story of how

a rider would start out when the sun's rim rose in the east and ride

until it fully set in the west. Anything inside this circle was

considered part of the grant.

Alas,

another fairy tale. During Spain's rule, the governor's simply marked

out an area the perspective soldier grantee felt he could work and

drew it up on a hand-sketched map. The grants increased radically

during Mexican rule as the Mexican government and governors used them

to pay back political favors. They were supposed to be landed estates

of the Mexican gentry but often lacked substance and certainly did

not have the massive, adobe structures we modern people think of.

The

entire system of large ranchos fell apart with the rise in power of

Americans who created first, the Republic of California or The Bear

Flag Revolt, but quickly lost out when General John Frémont showed

up and claimed it for the United States

And

yes, American Destiny carried forth in the claiming of California,

resulting in massive deaths of Indians who, up until the

secularization of the missions, had been protected by the friars. It

is something I find saddening in the history of my native land. The

very first order of the American governor was to round up all Indians

and force them onto reservations drawn up by local magistrates and

businessmen.

One

final myth was how American pirates had raided the coasts of

California, Oregon, and Washington. It was actually _French_-

pirates!

Growing

up in Southern California I took for granted the names of a lot of

places. I knew, for example, that Los Angeles somehow stood for the

City of the Queen of the Angels. I knew that Pico Boulevard was named

for a Mexican governor. I also thought that Palos Verdes stood for

Green Poles.

It

wasn't until I got into deep research for my Father Serra's Legacy

series that I began to learn much, more about the area of my birth

and childhood. Following are some examples:

Olvera

Street: Having started as a short lane, Wine Street, it was extended

and renamed in honor of Agustín Olvera, a prominent local judge, in

1877. That man was a descendant of Francisco Olvera, a servant in the

late 1700s. And, Wine Street was so named because of the profusion of

wild grapes in the area – they were cross-bred with grapes brought

from Spain.

Sepulveda

Boulevard, a major travel artery in the area that ends at San Pedro,

the vast ranch granted to the Sepulveda family via Juan Jose

Dominguez by Governor Fages. Juan came to LA as a cowboy from Villa

Sinaloa, Mexico. He was single and 53 years old. The Sepulveda family

were descendants of three lancers – soldados de cuera – who came

to California with the early expeditions. It is possible that one or

more of their children married Dominguez or his forefathers.

[A

word about this photo – it was taken about 1870, more than 60 years

after the founding of the rancho. But, it shows the lush grasses that

allowed for herds as big as 2,000 or 3,000 that roamed all throughout

Southern California – the vaqueros being California Indians who had

never even dreamed of the existence of horses or cattle less than a

hundred years earlier.]

And

then there is the town of La Habra. In the rancho days when vast

herds of Mexican cattle and horses grazed over the hills and valleys

of Southern California, Mariano Reyes Roldan was granted 6,698 acres

(27 km2) and named his land Rancho Cañada de La Habra. The year

was 1839, and the name referred to the “Pass Through the Hills,”

the natural pass to the north first discovered by Spanish explorers

in 1769. In the 1860s, Abel Stearns purchased Rancho La Habra. Soon

thereafter, heavy flooding followed by a severe drought brought

bankruptcy to many cattle ranchers.

I

certainly knew that any of the places named San or Santa had

something to do with Catholic saints. I just didn't know how that

came to be. I learned that, when a location of than a mission was

named, it was for the saint whose feast day it was on the Catholic

calendar.

I

certainly didn't know the history of the famous Beverly Hills. It

seems that a Luis Manuel Quintero, who came to California from

Guadalajara, Mexico, was a Poblador who signed up with

Captain/Governor Rivera. He was also a tailor who was there for the

founding of Royal Presidio of Santa Barbára and Mission San

Buenaventura. Three of his daughters married soldiers. A

granddaughter married Vincent Villa who became the owner of Rancho

Rodeo de las Augas on what it now known as Beverly Hills. I only

wonder if that was the source of the famous – and very exclusive –

Rodeo Drive. Perhaps the rancho's driveway?

I

also grew up with earthquakes being far more common than

thunderstorms. So, it was interesting to learn that, when Don

Gaspar's initial expedition came across a river they named after

Santa Ana, they encountered an earthquake and name the river as el

Rio de los Temblores or River of Tremors.

Redondo

Beach = after an original settler, Candelaria Redondo, widow of

Francisco Xavier Sepulveda. Probably one of her five children had a

rancho there.

El

Segundo? The second what? Aha! Here it is courtesy of Wikipedia: The

city earned its name ("the second" in Spanish) as it was

the site of the second Standard Oil refinery on the West Coast (the

first was at Richmond in northern California), when Standard Oil of

California purchased the 840 acres (3.4 km2) of farm land in 1911.

How

about Azusa? I always got a kick out of this from the song, Route 66.

Azusa originally referred to the San Gabriel Valley and river, and

likely derives from the Tongva place name Asuksagna. And then,

there's Cucamonga. The Mission Gabriel established the Rancho

Cucamonga as a site for grazing their cattle. In 1839, the rancho was

granted by the Mexican governor of California toTiburcio Tapia, a

wealthy Los Angeles merchant. Tapia transferred his cattle to

Cucamonga and built a fort-like adobe house on Red Hill. The Rancho

was inherited by Tapia's daughter, Maria Merced Tapia de Prudhomme,

and her husband Leon Victor Prudhomme. The name “Cucamonga” is

probably derived from a Tongva word for “sandy place.”

No comments:

Post a Comment