The

first thing to consider is the frugal life of the friars.

The

image of the short, plump balding friar, which

many people hold, was far from the case. Friars came in all

sizes and shapes. Each wore a gray colored robe (habit) made of wool

with a hood, the dress of a medieval beggar. Around his waist was

tied a rope known as a Cincture. The Cincture had three knots tied in

it to remind the friar of his vows of poverty, chastity and

obedience. Hanging from the Cincture was a rosary and cross so he

could pray and reflect upon the Mysteries of Christ's Life. He also

had a pouch to carry a few personal things, such as a prayer book or

journal; a large brimmed hat and a walking staff. A friar did not

carry or handle money nor did he ride a horse when traveling. Friars

traveled most of the time by foot, using a horse or donkey only for

long trips or those journeys with time constrictions. (A Day in

the Life of a Friar

by Tom Davis)

by Tom Davis)

So

what was the daily life of a friar like during the Mission period of

California? One thing for sure, it was not one of Sangrias and

Fandangos. Nor was it one of slave masters or sadistic over-lords who

saw the Native Californian as chattel. It was a life of hard work and

sacrifice, of cooperation and faith by all. The Franciscans of

California began and ended each day with prayer. As priests, they

made a promise to pray for the needs of the universal church as well

as for their own individual needs. Thus, seven times during the day

were set aside in which they prayed their prayers and the Divine

Office, starting as early as 2:00 am. They rose at sunrise and began

the day with Morning Prayer and meditation,

then celebrated mass around 7:00 am, followed by the Doctrina in the

Church. After church a simple breakfast. The friars ate bread, fresh

fruit, milk, eggs, vegetables, soup and, on special occasions,

cheese, fish and red meat.

Here

is their daily schedule”

9:00

am – Work with the children, teaching them religion, music,

language, etc.

10:00

am – Visit the sick and elderly.

11:00

am – Have their midday meal of fruit, soup, milk, and bread.

Usually gruel called atole.

12:00

noon – To pray the Angelus and other midday prayers. Followed by a

siesta of several hours – usually two.

2:00

pm – Friars continued to visit, counsel or write letters and

reports.

3:00

pm – Say the Rosary or other prayers and devotions.

4:00

pm – Worked with children, especially instructing them in music or

games.

5:00

pm – More prayers and the Doctrina in the Chapel

6:00

pm – recite Vespers or evening prayer

7:00

pm - Light evening meal of soup, bread, or fruit. They

would then relax, read, play cards of socialize until night prayer

and bed, usually not much later than 9:00 pm. They would then

awaken at 2:00 am to start all over again.

In

many cases, the socializing might be enjoying the evening

entertainment by local musicians in the mission plaza.

The

friars shared their own personal talents and hobbies with the Native

Californians, showing the Indians, for example, how to paint, sing,

and play musical instruments. The friars shared their lives with

those they came to serve and learned to love.

Mission

San Diego in background

Daily Life of Missionaries

Each

mission had two friars with an escort of five presidials [the

soldados de cuera] led by a corporal. As much as possible, an

effort was made to assign soldiers with wives and children. The

single ones served at the presidios.

Life

at the California missions varied slightly throughout the entire

system. Once a "gentile" was baptized, he or she became a

neophyte, or new believer. This happened only after a brief period

during which the initiates were instructed in the most basic aspects

of the Catholic faith. However, while many natives were lured to join

the missions out of curiosity and sincere desire to participate and

engage in trade, many found themselves trapped once they received the

sacrament of baptism. To the padres, a baptized Indian was no longer

free to move about the country, but had to labor and worship at the

mission under the strict observance of the fathers and overseers, who

herded them to daily masses and labors. If an Indian did not report

for their duties for a period of a few days, they were searched for,

and if it was discovered that they left without permission, they were

considered runaways. Some were allowed to return to their home

villages for certain important events such as planting or harvest –

and some religious events.

Any

of those who left without permission were hunted down by the

presidials and returned to the mission for punishment. NO, they were

NOT whipped! Most punishment, as indicated in earlier posts, was

public humiliation and possibly being placed in solitude for a

period. In certain cases, they would be publicly “spanked”,

another form of humiliation. In all cases, the friars spent

considerable time explaining what the failure was to the miscreant

and the congregation. The friars punished neophytes for other

offenses too, such as lack of attention in worship services. They

used whipping, confinement in stocks and other punishments they

thought necessary to Christianize the Native Americans.

Sadly,

unmarried women were locked in women’s quarters each night at the

mission to prevent what the priests called promiscuity. This is

because most California Indians did not believe in marriage in the

European sense. Indian women selected their mates for survival traits

and, when the mate did not perform, simply walked away and found

another. This is one of the reasons they suffered from forms of

venereal disease long before the arrival of the Spanish.

Why

did the friars keep their baptized Indians close to the mission?

First,

it was The Law of the Indies

Secondly,

the missionaries had the gravest obligation to give them religious

instruction.

Thirdly,

they were burdened, not only with the duty of pastors, but also the

responsibility of parents.

The

friars allowed their neophytes to go home for 5 or 6 weeks per year

but did not want them to have prolonged contact with un-Christianized

Indians. They came under the Fourth Commandment of Honor thy father

and mother, which the friars could not refuse.

First

and foremost, the friars had parental responsibility for the Indians

and failing to act to correct their sins placed those sins, in The

Eye of God, strictly upon their backs!

For

their part, the Indians were accustomed to have no set hours for

anything to include breakfast, lunch or dinner but to spend the

greater part of each day simply searching for food. They did not have

a regular, reliable source of sustenance and were subject to the

whims of nature. The faults that needed correction included theft of

property from those who lived outside the tribal unit, divorce and

remarriage for little or no reason, indulgence in promiscuity and, in

some tribelets, in homosexuality, the practice of abortion, and in

the tradition of taking human life as punishment for personal

injuries.

Bells

were vitally important to daily life at any mission.

The

bells were rung at mealtimes, to call the Mission residents to work

and to religious services, during births and funerals, to signal the

approach of a ship or returning missionary, and at other times;

novices were instructed in the intricate rituals associated with the

ringing the mission bells. The daily routine began with sunrise Mass

and morning prayers, followed by instruction of the natives in the

teachings of the Roman Catholic faith. After a generous (by era

standards) breakfast of atole, [cornmeal] the able-bodied men and

women were assigned their tasks for the day. The

women were committed to dressmaking, knitting, weaving, embroidering,

laundering, and cooking, while some of the stronger girls would grind

flour or carry adobe bricks (weighing 55 lb, or 25 kg each) to the

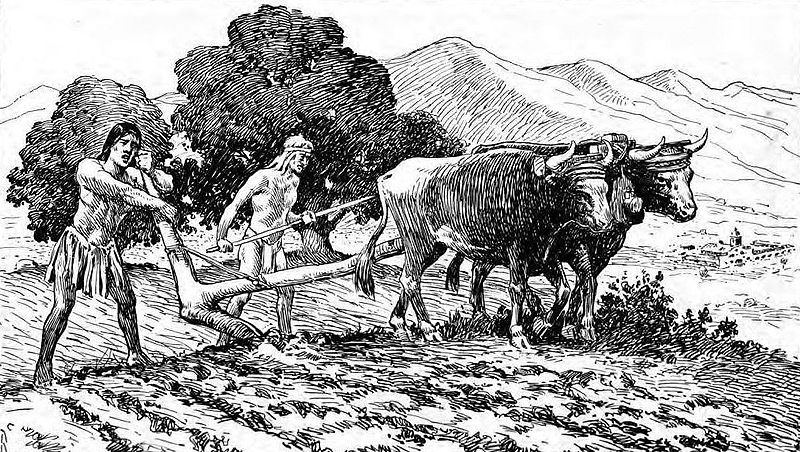

men engaged in building. The men were tasked with a variety of jobs,

having learned from the missionaries how to plow, sow, irrigate,

cultivate, reap, thresh, and glean. In addition, they were taught to

build adobe houses, tan leather hides, shear sheep, weave rugs and

clothing from wool, make ropes, soap, paint, and other useful duties.

The

goal of the missions was, above all, to become self-sufficient in

relatively short order. Farming, therefore, was the most important

industry of any mission. {That was good as most of the Franciscans

came from farms or farming villages] Barley, maize, and wheat were

among the most common crops grown. Cereal grains were dried and

ground by stone into flour. Even today, California is well known for

the abundance and many varieties of fruit trees that are cultivated

throughout the state. The only fruits indigenous to the region,

however, consisted of wild berries or grew on small bushes. Spanish

missionaries brought fruit seeds over from Europe, many of which had

been introduced to the Old World from Asia following earlier

expeditions to the continent; orange, grape, apple, peach, pear, and

fig seeds were among the most prolific of the imports. Grapes were

also grown and fermented into wine for sacramental use and again, for

trading. The specific variety, called the Criolla or "Mission

grape," was first planted at Mission San Juan Capistrano in

1779; in 1783, the first wine produced in Alta California emerged

from the mission's winery.

Mission

San Gabriel Arcángel would unknowingly witness the origin of the

California citrus industry with the planting of the region’s first

significant orchard in 1804, though the commercial potential of

citrus would not be realized until 1841. Olives (first cultivated at

Mission San Diego de Alcalá) were grown, cured, and pressed under

large stone wheels to extract their oil, both for use at the mission

and to trade for other goods. Father Serra set aside a portion of the

Mission Carmel gardens in 1774 for tobacco plants, a practice which

soon spread throughout the mission system.

It

was also the missions' responsibility to provide the Spanish forts,

or "presidios", with the necessary foodstuffs, and

manufactured goods to sustain operations. It was a constant point of

contention between missionaries and the soldiers as to how many

fanegas of barley, or how many shirts or blankets the mission

had to provide the garrisons on any given year. At times, these

requirements were hard to meet, especially during years of drought,

or when the much-anticipated shipments from the port of San Blas

failed to arrive. The Spaniards kept meticulous records of mission

activities, and each year reports submitted to the Father-President

summarizing both the material and spiritual status at each of the

settlements.

Livestock

was raised, not only for the purpose of obtaining meat, but also for

wool, leather, and tallow, and for cultivating the land. In 1832, at

the height of their prosperity, the missions collectively owned:

151,180

head of cattle;

137,969

sheep;

14,522

horses;

1,575

mules or burros;

1,711

goats; and

1,164

swine.

All

of these animals were originally brought up from Mexico. A great many

Indians were required to guard the herds and flocks, which created

the need for "...a class of horsemen scarcely surpassed

anywhere." These animals multiplied beyond the settler's

expectations, often overrunning pastures and extending well-beyond

the domains of the missions. The giant herds of horses and cows took

well to the climate and the extensive pastures of the Coastal

California region, but at a heavy price for the Native inhabitants.

The uncontrolled spread of these new species quickly exhausted the

grasslands and hillsides the Indians depended on for their seed

harvests. This problem was also recognized by the Spaniards

themselves, who at times sent out extermination parties to kill

thousands of excess livestock, when the populations grew beyond their

control. Mission kitchens and bakeries prepared and served thousands

of meals each day.

Candles,

soap, grease, and ointments were all made from tallow (rendered

animal fat) in large vats located just outside the west wing. Also

situated in this general area were vats for dyeing wool and tanning

leather, and primitive looms for weaving. Large bodegas (warehouses)

provided long-term storage for preserved foodstuffs and other treated

materials.

Each

mission had to fabricate virtually all of its construction materials

from local materials. Workers in the carpintería (carpentry

shop) used crude methods to shape beams, lintels, and other

structural elements; more skilled artisans carved doors, furniture,

and wooden implements. For certain applications bricks (ladrillos)

were fired in ovens (kilns) to strengthen them and make them more

resistant to the elements; when tejas (roof tiles) eventually

replaced the conventional jacal roofing (densely packed reeds)

they were placed in the kilns to harden them as well. Glazed ceramic

pots, dishes, and canisters were also made in mission kilns.

I'll

leave it to the reader to determine the pluses and minuses of this

era. Did the loss of their native ways somehow destroy an important

stage of society? Or did brining Europeans ways improve their lives?

Were the restrictions fair or a form of slavery as some modern

apologists call it?

In

any cases, what are your views of this? Love to hear them.

No comments:

Post a Comment