I've been posting

about the California Missions in Alta

or Upper California and have bypassed the original ones established

in Baja, or Lower

California.

The

first mission established in The Californias [note the plural] was

the Misión

Nuestra Senora de Loreto Conchó, founded on October 19, 1697 by the

Jesuit priest Juan María de Salvatierra – a good seventy years

before Father Serra came on the scene. The town of Loreto went on to

become the religious and administrative capital of The Californias.

When

we think of “Governor” Portola, we often miss the point that he

was actually the Lieutenant Governor for Alta California. The

“governor” was actually Matias

de Armona who presided at Loreto – with no direct authority over

Portola, or Fages who followed.

Armona was openly hostile to the Franciscans, feeling the Jesuits who

were ousted, had been unfairly treated. This bitterness caused him to

be removed in 1775.

Those

who have visited Baja know it to be an arid, hostile land where every

plant reaches out to snag, grab, or sting you. What few animals that

live there are nocturnal. Those you might see during the day will

poison you with their venom. At the same time, the oceans surrounding

it contain some truly amazing and beautiful creatures. Sharks as big

as whales – without teeth! Giant Oceanic Manta Rays as big as some

light airplanes that fly awesomely through the Sea of Cortez.

Swordfish. Tuna. And massive gatherings of Hammerhead Sharks.

The

mission at Loreto was the basis for the other missions in both upper

and lower California and was based upon similar missions founded by

the Jesuits wherever they served. The other orders, Franciscan,

Dominicans, and Capuchins followed their model.

It

should also be remember that, at the time of the founding of the

missions in Baja, the weather was far different than in the 1800s and

today. The world was in the midst of The Mini Ice Age, a time when

lakes and rivers in Europe and North America froze solid for lengthy

periods and winters were especially long and cold. Sub-tropical areas

such as the American southwest, northern Mexico, and The Californias

were cooler with more abundant water. So, the missions were able to

sustain themselves then, while many have been abandoned.

These

were the natives who lived in Baja. Their lives were even more

primitive than other tribes to the north and east of them. They had

not progressed beyond the Stone Age and lived strictly by what nature

provided. They proliferated in times of plenty and died away in times

of drought – just like the plants and animals they lived with.

El

Camino

Real Misionero

The

road connecting the missions in Upper California was called El

Camino Real,

The King's Highway, while the one in Lower California was called The

Royal Missionary Highway/Path, whichever is most commonly used. It

was just that, a narrow pathway for the Jesuits to move from mission

to mission, often riding mules or donkeys. It was never designed for

wheeled vehicles and often crossed extremely rugged terrain.

After

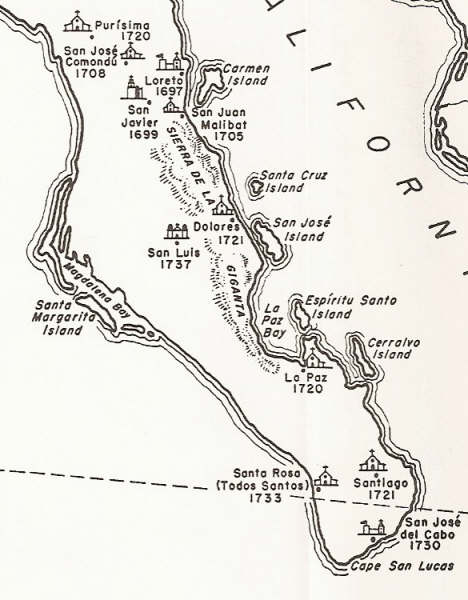

founding the mission at Loreto, the Jesuits went on to establish

seventeen more, plus two ranchos and/or visitas [visiting stations or

country chapels which a priest might show up irregularly].

Without

a topographic map, it is extremely difficult to relate to just how

rugged and difficult the terrain and how the priests managed to make

their way from one to another.

This

is only the southern part of Baja and it is easy to see how separated

these missions are/were – some no longer stand.

I

think all of us are familiar with Cabo San Lucas and become confused

to learn the airport is actually in San José

del Cabo, or where the mission is actually located. And, the name of

the mission founded at the Pericú settlement of Añuití in 1730 by

Jesuit Father Nicolá Tamaral, is a real mouthful - Misión Estero

de las Palmas de San José del Cabo Añuití. A presidio, or military

base, was also located there.

The

most serious rebellion in the southern part of the Baja Peninsula

took place in 1734-1737. This uprising of the Pericú and Guaycuras

engulfed several missions in the southern part of the peninsula, most

of which had to be abandoned. In January 1735, indigenous forces

ambushed the Manila Galleon that had stopped at San José del Cabo

for supplies. "The revolt and its subsequent suppression,"

according to Don Laylander, "hastened the disorganization and

declines of the southern aboriginal groups. To suppress the revolt,

the Jesuits were forced to call in outside military assistance."

In 1742, King Felipe V authorized the use of royal funds to suppress

the revolt. The arrival of a military force from Sinaloa helped to

restore order and reestablish control of the southern Baja lands. The

last scattered resistance to the Spaniards did not end until 1744.

Misión San José del Cabo was re-established in 1736 as a visita of

Mission Santiago, and finally closed in 1840 by the Mexicans.

In

1990, I loaded my wife and her five kids into my 1964 Dodge 400

station wagon. We took the car ferry from Mazatlan to La Paz. We were

in a hurry to get to Tijuana so we only drove past la Misión de

Nuestra Señora del Pilar de La Paz Airapí, established by the the

Jesuit missionaries Juan de Ugarte and Jaime Bravo in 1720. It was

also involved in the Pericú and Guaycura revolt. All of its Indian

neophytes and disciples were relocated to Misión Santa Rosa de las

Palmas in Todos Santo.

Franciscans

establish their only mission

[The only pictures are of some adobe brick piles]

In

1769, on orders of Visitador Galvez, Father Serra led an expedition

north to establish Misión San Fernando Rey de España de Velicatá,

the only Franciscan mission in Baja. In the 1770s, under the

Franciscans and then after 1773 under their Dominican successors, the

mission quickly reached its peak and went into decline as epidemics

decimated the native population. A missionary was no longer

permanently resident at the site after about 1818. A few ruined walls

and stone foundations survive at the site as well as petroglyphs and

some remains of pictograms.

Representatives

of the Dominican order arrived in 1772

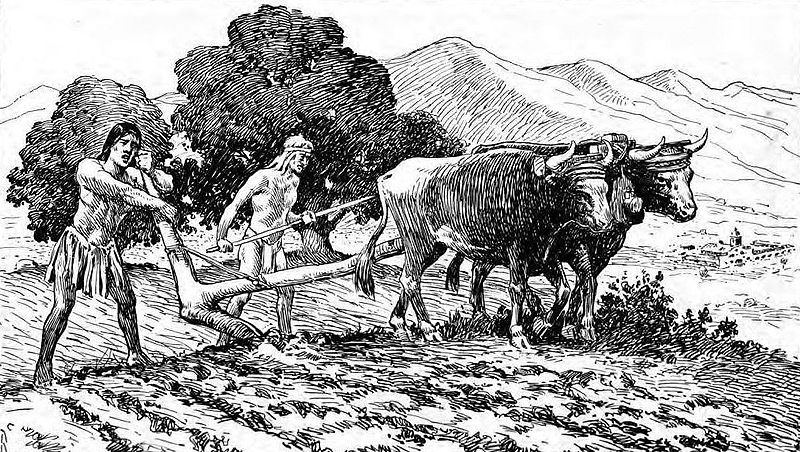

To

Loreto came more and more fathers from many countries of Europe, as

the work

expanded

west over the steep ridges of La Giganta. The usual procedure in

founding a

mission

was to find a suitable site with water and pasturage. Trails had to

be hacked out

for

mule trains bringing supplies from the mother mission. Then Indians

were gathered

and

with their help buildings erected and crops sown. Ingenious systems

of irrigation

were

devised. But on Baja California there was always a struggle with the

elements.

Drought

caused springs to dry up and crops to wither; because of it many a

mission had to move its site. Torrential rains brought floods to wash

away the hard-won fields; winds of hurricane force knocked down the

first crude buildings. If the weather proved kind, along came swarms

of locusts to strip the green leaves from every growing thing. After

years of struggle, however, the fathers could point proudly to

orchards, patches of vegetables and melons, date palms - some of

which still survive - fields of grain, sugar-cane and cotton, flocks

of cattle, sheep, horses and mules. Over the rough trails the fathers

went forth to found new missions north and south.

The

Dominican mission closest to the Mexican/Californian border is Misión

El Descanso or Misión San Miguel la Nueva founded in 1817 at a site

about 22 kilometers south of present-day Rosarito. It was the last

founded by the Dominicans and the furthest north.

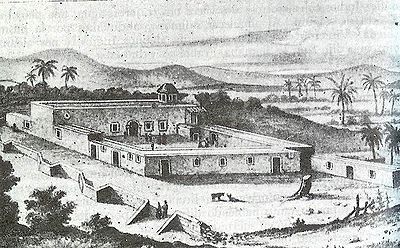

This

is an artist's depictions of what the mission garden once looked

like.

Sadly,

wind, weather and political considerations have laid waste of many of

those missions in the arid deserts of Baja. Those in the best

condition are still places of worship for the heavily Roman Catholic

population. Here are some pictures of those currently in service as

churches:

Misión

de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe del Norte

Misión

San Francisco Borja

Misión

Santa Gertrudis

Misión

San Ignacio Kadakaamán

Misión

Santa Rosalía de Mulegé

Misión

San Francisco Javier de Viggé-Biaundó

Misión

San Luis Gonzaga Chiriyaqui

If

you really want a taste of history, these are well worthwhile

visiting.